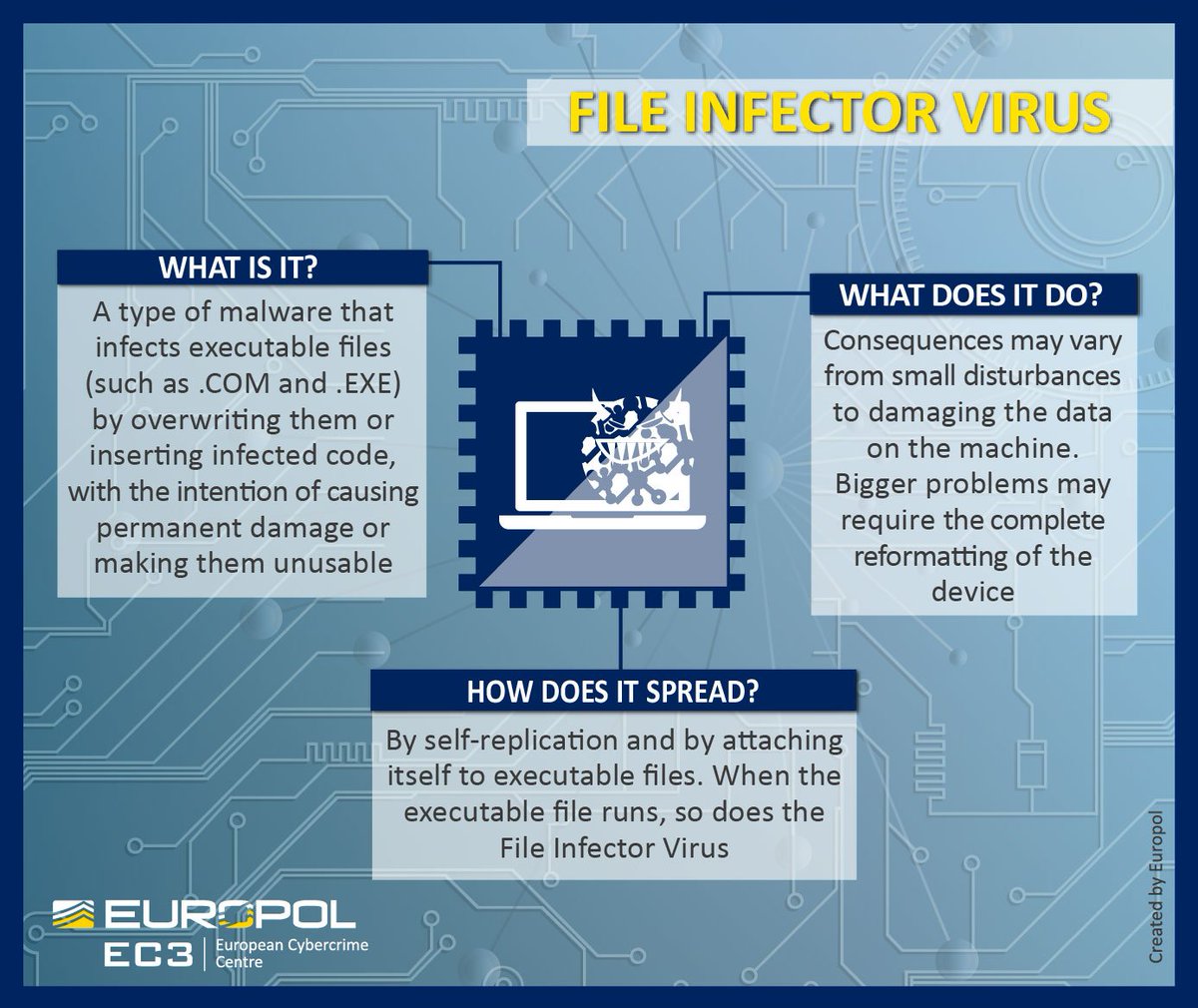

I first encountered the idea of a file infector virus while reading incident reports from the late 1990s, when computers still shared software on disks and email attachments arrived without warning banners. An infector virus, also known as a file infector virus, is malware that attaches its malicious code to legitimate executable files such as .exe or .dll. When a user launches an infected file, the virus activates, copies itself into other executables, and may deliver a destructive payload. Unlike worms, which spread independently across networks, infectors depend on a host file and human action to move.

For readers searching today, the intent is clear and urgent. What is an infector virus, how dangerous is it, and what should I do if I suspect one on my system? These questions persist because infectors represent a particularly insidious class of malware. They corrupt the very files users trust most. Antivirus cleanup is harder, data recovery is riskier, and false confidence is common.

Although modern operating systems have improved protections, file infectors still appear, especially on poorly patched systems or removable media. Understanding how they work is essential for prevention and safe removal. This article traces their mechanics, historic impact, detection methods, and the disciplined steps required to remove them without making damage worse.

Read: Skype Vox Explained: Vox.io, Voice Control, and History

What an Infector Virus Really Does

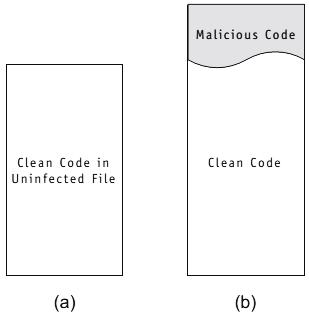

An infector virus does not arrive as a standalone program. Instead, it embeds itself into a legitimate executable file. When that file runs, the virus code executes first or alongside the original program. From there, it searches for other executables to infect, often in the same directory or across the system.

This behavior makes infectors uniquely dangerous. Each infected file becomes a carrier. Deleting the wrong executable can break applications or the operating system itself. In early Windows environments, this often meant total system failure.

Security historian Fred Cohen, who coined the term “computer virus” in the 1980s, described file infectors as the purest form of self-replicating malware. They rely on trust and routine rather than network exploits.

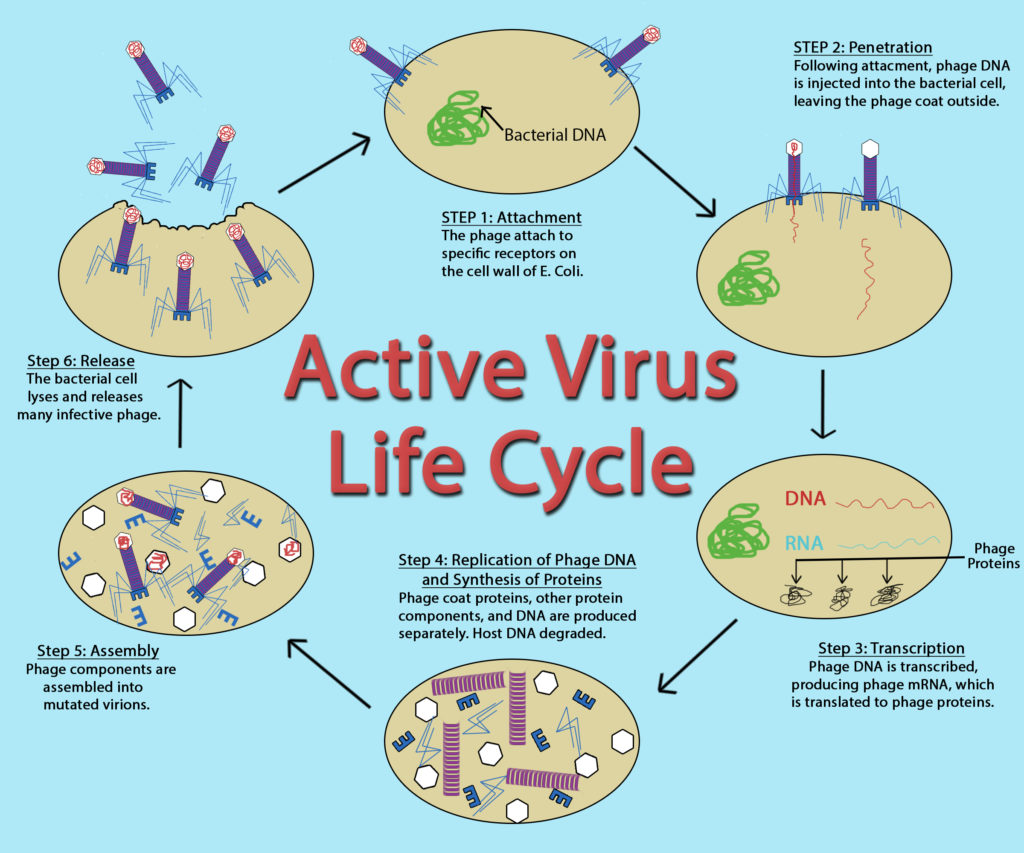

The Infection Cycle Explained

Infector viruses follow a predictable lifecycle. First comes attachment, where the virus inserts code into a host file. Next is activation, triggered when the infected file runs. Replication follows, spreading the virus to other executables. Finally, the payload may execute, ranging from benign messages to destructive actions.

This cycle differentiates infectors from worms. Worms exploit vulnerabilities to spread automatically. Infectors wait patiently for execution. That patience is what allowed them to survive in early computing environments with limited defenses.

Malware analyst Mikko Hyppönen has noted that infectors thrived when software sharing was common and security hygiene was minimal. Their decline reflects cultural as much as technical change.

Read: DVI Cable Explained: Types, Limits, and Uses

Common Types of Infector Viruses

Not all infectors behave the same. Direct-action infectors activate, infect nearby files, then go dormant. The historic Vienna virus is a classic example. Sparse infectors spread intermittently to evade detection, making corruption harder to trace.

Multipartite infectors target both files and boot sectors, complicating removal. Fast or polymorphic infectors mutate their code or rapidly infect files during scans, frustrating signature-based antivirus tools.

Each type reflects an evolutionary response to detection.

Table: Major Infector Virus Types

| Type | Behavior | Detection Difficulty |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Action | Infects then sleeps | Low |

| Sparse | Intermittent infection | Medium |

| Multipartite | Files + boot sectors | High |

| Polymorphic | Code mutation | Very High |

Historic Infector Viruses That Changed Security

Some infector viruses reshaped cybersecurity awareness. The Vienna virus in 1986 was among the first widely observed file infectors. The Jerusalem virus followed, activating on Fridays the 13th, slowing systems and deleting files.

The CIH, or Chernobyl virus, released in 1998, was especially destructive. It overwrote critical system data and, on some systems, corrupted BIOS firmware, rendering computers unbootable. That event marked a turning point, pushing vendors toward stronger protections.

Modern Survivors Like Sality

While many classic infectors faded, some persisted. Sality, first identified in 2003, remains notable. It is a polymorphic file infector that disables security tools, encrypts files, and forms botnets. Its resilience demonstrates that file infectors never fully disappeared.

Security researcher Eugene Kaspersky has described Sality as evidence that old techniques still work when paired with modern obfuscation.

Behavioral Signs of Infection

Detecting infectors requires attention to subtle changes. Executable files may grow slightly in size. System files show unexpected modification dates. Performance degrades as replication consumes resources.

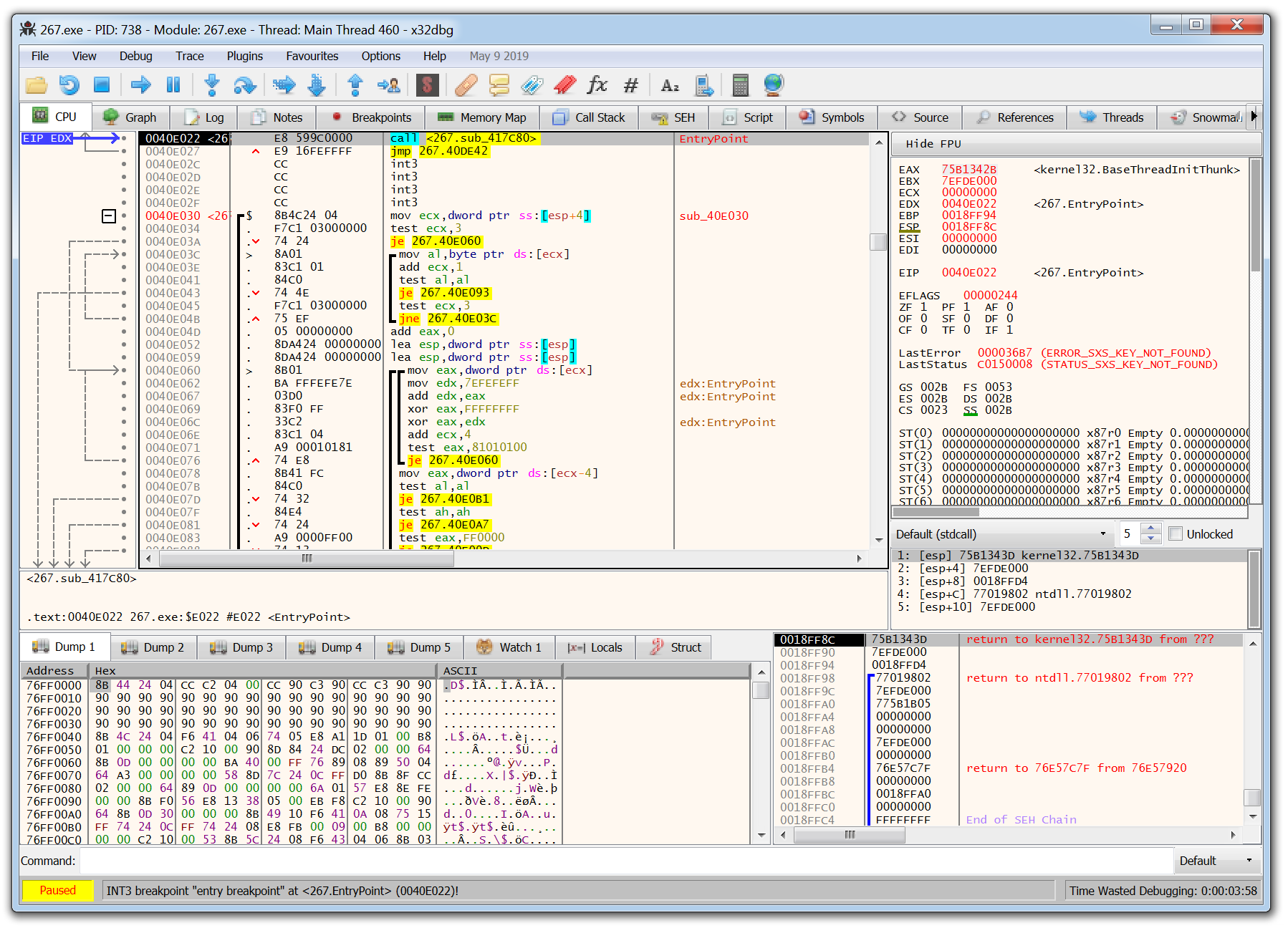

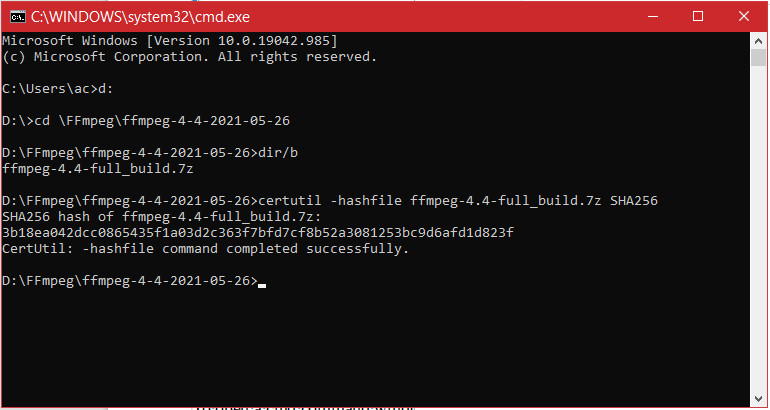

Sorting system folders by date modified can reveal anomalies. Hash comparisons using tools like certutil help verify file integrity. These techniques are often used by forensic analysts.

Primary Scanning Methods

Modern Windows systems include built-in defenses. A full scan or Microsoft Defender Offline scan can detect many infectors by combining signatures and heuristics. Running scans in Safe Mode limits malware activity.

Security professionals often recommend a second opinion scan using reputable tools to reduce false negatives. Careful review of quarantined files is essential, especially for polymorphic threats.

Table: Detection and Verification Tools

| Tool | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Windows Security | Primary detection |

| Offline Scan | Root-level threats |

| Malwarebytes | Secondary verification |

| sfc /scannow | Repair system files |

Safe Removal Strategy

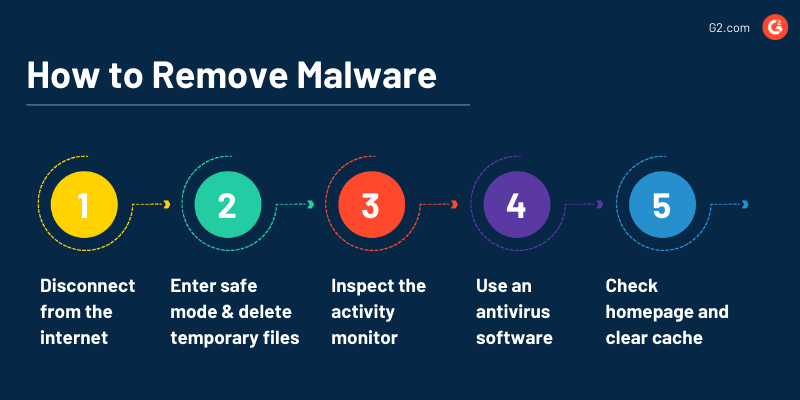

Removing an infector virus requires restraint. Disconnecting from the internet prevents further spread. Booting into Safe Mode reduces execution opportunities. Automated tools should be used before manual deletion.

Manually deleting infected executables risks breaking applications. Backups must be scanned before restoration. In severe cases, a full system reset may be the safest option.

Incident responder Brian Krebs has warned that impatience during cleanup often causes more harm than the malware itself.

Command-Line Inspection

Advanced users may inspect drives via Command Prompt. Revealing hidden files and checking attributes can expose suspicious executables. Hashing known-good files allows comparison against trusted baselines.

These steps are diagnostic, not a substitute for antivirus remediation.

Prevention in Modern Environments

Prevention remains the most effective defense. Updated antivirus software, system patching, and cautious handling of removable media reduce risk. In enterprise settings, network segmentation and application whitelisting limit spread.

Infector viruses thrive where trust is misplaced.

Takeaways

- Infector viruses attach to legitimate executable files.

- They require user execution to spread.

- Historic outbreaks shaped modern security practices.

- Detection relies on behavioral and heuristic analysis.

- Removal must prioritize automation over manual deletion.

- Prevention depends on updates, scanning, and discipline.

Conclusion

I see infector viruses as reminders of an earlier internet, when trust was implicit and defenses were thin. Their legacy endures not because they were clever, but because they exploited human habits. Today’s systems are stronger, yet the underlying lesson remains. Malware succeeds when users assume safety.

Understanding infectors is not about nostalgia. It is about recognizing how deeply malware can integrate into trusted systems. The more we understand their behavior, the less power they hold.

FAQs

What is a file infector virus?

Malware that attaches itself to executable files and spreads when they run.

Are infectors still a threat today?

Yes, though less common, they persist on poorly protected systems.

Can antivirus remove infectors safely?

Often yes, especially using offline or Safe Mode scans.

Should I manually delete infected files?

Only with caution. Automated tools are safer.

Is data recovery possible after infection?

Sometimes, but infected executables may need replacement.